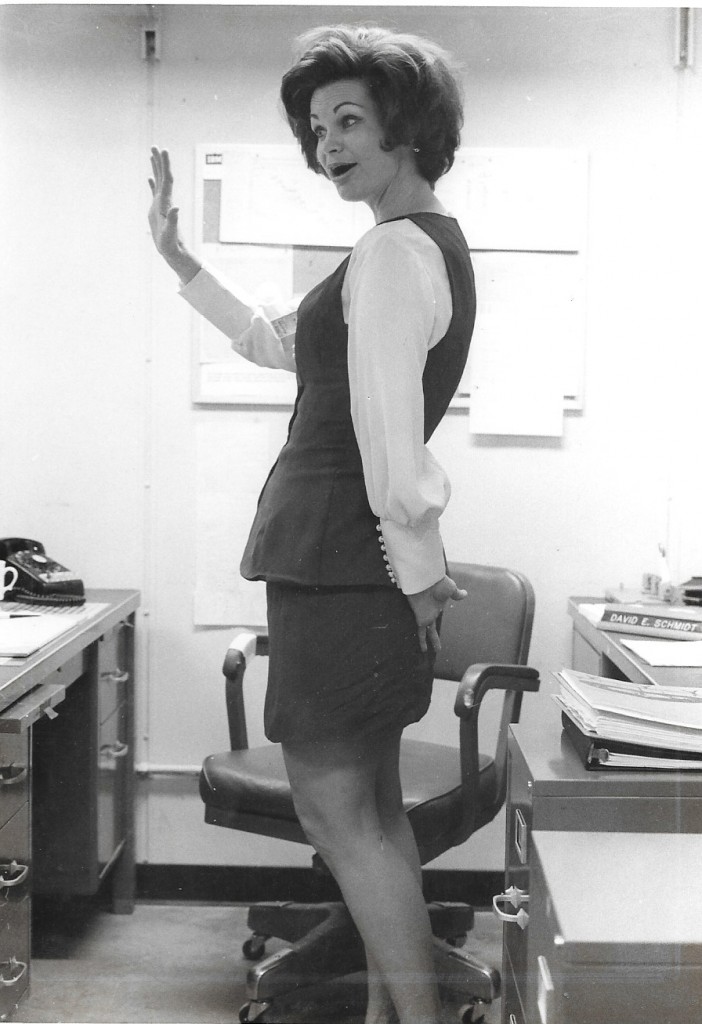

Martha Lemasters, author of The Step, at work for IBM at the Kennedy Space Center during the Apollo Progam.

By the 1970s, pantyhose were a staple in every woman’s wardrobe. As more women headed into the workplace, sales of pantyhose grew. The only problem was that there wasn’t very good elastic in the waist and they would start to droop to your hips if you didn’t pull them up!

The day has finally arrived for my first business trip. I am to go to Bethesda, Maryland, just outside D.C., to sit in for the communications manager for one week. I am confident. I have learned to become assertive and stand up for my rights. I am so excited; I feel I’ve earned this trip. I know I’m a professional woman now. I’ve developed my creativity and knowledge. I pick out my best business suit to wear; every strand of hair is in place. Even my attaché case matches the overnight bag I carry. In short, Doris Day couldn’t look any more perfect for the part of a traveling professional woman.

I am to leave from the Melbourne airport, fly to Atlanta for a change to Washington, D.C. I check my suitcase, board the plane and I’m on my way. I expect the trip to be easy but once over Atlanta we have to circle the airport for more than an hour, slipping my boarding time for my next flight to D.C. I now have only three to four minutes to make that flight.

As I descend the stairs from the plane, I think I can make it. I am feeling important as I look around and see most of the passengers are men. I hold my head up high and then it happens. With my overnight case in one hand and my attaché case, as well as my huge handbag in another, the elastic in my pantyhose breaks. Hovering over I use both elbows to pinch each side of the pantyhose to keep them from falling down. Hurrying through the airport the vision is not exactly what would appear on the cover of New Woman Magazine. My 5’9” frame stooping over, elbows in place holding the pantyhose up and scurrying as fast as I can. I know I don’t have time to stop and take the pantyhose off because I will miss my flight. I finally make it to the plane. One of the flight attendants comes over and asks “Are you in pain”?

“No, I just need to get to the ladies room and remove these pantyhose.”

I’d been warned me about the D.C. airport: “It’s one of the most hectic airports you’ll ever go through. The secret is to get to the rental car agency and get out of the airport before the 5 p.m. rush-hour traffic begins.”

With these words ingrained in my thoughts, I make a beeline to the rental car agency as soon as I land. I get the keys and hurry to the huge parking lot. It takes me a while to even find the car; then I have trouble getting the car started. A man passes by and I ask him if he knows the secret to starting the car.

“You’ve got to have your seat belt on,” he says.

I feel so ignorant. But I think the procedure, obviously installed by the rental company, even more stupid. I get started and head out of Washington. I travel about 30 miles, happy that I’ve beaten the worst of traffic when it hits me. I have forgotten my suitcase! As I approach a road sign that reads Manassas, I realize I have also traveled south, instead of north. I travel for another few miles before I can get off and turn around to go back to the airport. My lips start to quiver, tears are coming down my face, destroying my image as a professional woman entirely.

As I pull up to the area designated for arriving passengers, the porter comes up to the window of my car and all my professionalism goes out the window. My chin is even quivering, my bottom lip protrudes and I just break out crying. “I left my luggage in the airport, drove 30 miles in the wrong direction and I don’t know how to get my luggage or even get out of this place and drive the right direction. Can you please help me”?

“Of course I can,” he says gently. “Let me have your claim ticket.” I quit sniffling, give him my ticket and wait in the car. In a short time, he returns with my suitcase and puts it in the back seat.

“Now, where is it you’re supposed to go,” he says.

“Bethesda,” I softly answer as I hand him a $10 tip. Well, so much for being professional.

I finally reach the six-story hotel and check in. It is December and I think it’s very cold but then I’m a Florida gal, I think it’s winter when the temperature reaches the fifties. The temperature is 31 and sinking according to the TV in my room. I decide to eat in the hotel restaurant not wanting to venture out on such a cold evening. After dinner I go to bed early to get a full night’s rest so I can make a dynamic impression with my energy and promptness the next morning.

Talk in the next room awakens me. I glance over at the red dial on the clock and see that its 2 a.m. I imagine the talking is from a late night party someone is having, as I can even smell the smoke from their cigars and cigarettes.

I plug some Kleenex into my ears and turn over hoping to fall back asleep. A loud siren jolts me out of bed. I suppose it’s someone stuck in the elevator. I put the pillow over my head but the sound is too penetrating. I pick up the phone and call the front desk. “Is someone caught in the elevator? The bell on my floor keeps ringing.”

“The hotel is on fire! Get a coat on and evacuate the building at once,” comes his frantic cry. I am dressed in my Florida-style shorty nightgown. My coat, also made for Florida, is thin and falls just below my waist. I packed my new bra and my new tennis racquet. It is a toss-up as to which item to grab to take with me. I put my coat on and grab my beloved racquet and purse and head out the door to the deafening sound of the siren. I am also barefooted and barelegged. The hallway is filled with men, some half-dressed, some half-asleep, some half-drunk, all very anxious. They all head to the elevator. “No,” I yell, remembering my safety training. “We have to take the stairs.” About 30 people cram down the stairs, jumping two and three steps at a time. Once outside I see five fire trucks surrounding the building. One is a hook and ladder, perched at the top floor with the fireman knocking on the window, trying to wake up the people inside.

It is freezing and there is no place to go inside. Out of the whole crowd of hundreds there are three women. At least they have on full-length warm coats. I notice the strange things that the crowd has managed to bring with them: bottles of scotch, whisky, shoes in hand. And I stand here with my racquet.

The fire department is providing oxygen to some of the people who have inhaled smoke. One fireman comes over and asks, if I need artificial respiration. I wonder why he is asking me that, I’m not coughing or slow of breath. I relate it to walking across the catwalk at the VAB.

About 30 minutes later a school bus is brought in for us to get out of the weather. There is no heat in the school bus but at least we can sit down. By dawn, we are told that we can’t go back into the hotel to get any belongings. I put a call into my work contact and tell him what’s happened. Then I utter the words that no professional woman wants to say. “I have no clothes, can you possibly ask around the office to see if someone in a size 12 can loan me a dress for just the day? Oh, and a pair of shoes in size 9.”

Gene, my contact, arrives in about an hour with a green and blue stripe dress and shoes. The shoes weren’t too bad. The dress was about two inches short-waisted and another two inches too short in length. It was also very tight around my hips. I looked like a refugee from Goodwill. Decked out like this, I drove the car to the building and head straight to the receptionist. I resolve to hold my head up and just get on with the day.

“Can you direct me to the Personnel Office,” I ask.

“Oh honey,” she replies, as she looks me up and then down. “We’re not hiring today.

I am reminded of a date in time: August 26, 1971. I was working at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) as a member of the Apollo Launch Support Team. At the behest of Rep. Bella Abzug (D-NY) Congress designated August 26 as “Women’s Equality Day.”

I am reminded of a date in time: August 26, 1971. I was working at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) as a member of the Apollo Launch Support Team. At the behest of Rep. Bella Abzug (D-NY) Congress designated August 26 as “Women’s Equality Day.” Huntsville

Huntsville Cape Kennedy

Cape Kennedy Houston

Houston

Goddard

Goddard